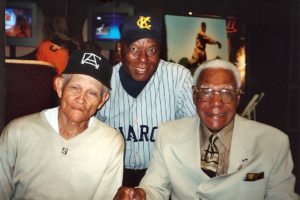

My friend, Neale “Bobo” Henderson, was San Diego’s last former Negro League baseball player. He passed on December 27, 2018 at age 88. Neale was preceded in death by former local Negro Leaguers: Johnny Ritchey, Walter McCoy and Gene Richardson.

These men did not particularly appreciate being identified as “African-Americans,” but preferred to be known as Americans. Neale, Walter and Johnny all served in the U.S. Army during wartime. They were also proud to be recognized as former Negro League ballplayers.

We live in a politically correct minefield.

People have objected to me using the words “Negro Leagues” in my talks about the history of “African-American” baseball. In my opinion, they are ill-informed, because they do not fully understand the sacrifice, perseverance and character of previous generations.

Bobo’s life was celebrated at Mt. Erie Baptist Church in Southeast San Diego. Every pew was filled.

KUSI-TV sports reporter Brandon Stone covered the service and captured the tone in his broadcast with this humorous anecdote.

“Neale Henderson stopped being Neale Henderson the day his mother let another woman see her baby. She said, ‘Your baby looks like Bobo the Clown.'”

The name stuck. Ballplayers don’t have colorful nicknames anymore.

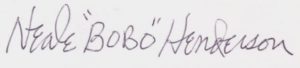

Furthermore, if and when modern players do sign autographs, you can’t read them.

In the old days, ballplayers took pride in their distinctive penmanship. When Neale signed a baseball, his signature was easy to read. The letters were clearly formed and uniform: Neale “BOBO” Henderson.

It’s true that Bobo could play the clown, but he was not a screwball. Nevertheless, he tended to throw knuckleballs when he spoke. That’s because nobody, including Bo himself, knew for sure what was going to happen when his mouth opened.

He enjoyed making people laugh, making them comfortable, often at his own expense. And, oh, how he loved kids… and they loved him, too. He recognized baseball players were supposed to be heroes to kids. Bobo relished the role.

You had to smile when you were around this man. He loved to tell stories. There’s a saying among ballplayers: the older they get, the better they were. A relative once described his 98-year-old former professional ballplayer uncle as having a remarkable memory.

“His memory is so good, he even remembers things that didn’t happen.”

That would describe Neale. His son, Paul, recalls that his dad loved to get together with friends and “swap lies.”

I’d never call Neale a liar, but the man sure could exaggerate. It was a tendency that drove the stolid Mr. Walter McCoy to distraction. When we were together, I had to keep them separated.

Neale’s daughter asked me to speak at the funeral and the first thing my wife said was, “You’re not telling that story in church!”

The story involved Bobo unintentionally using profanity during a live TV interview at the San Diego Hall of Champions.

It was funny, but the Hall had just entered a partnership with Aflac Insurance Company to bring their high school All-American Game to San Diego. Hall of Champions director Al Kidd knew he had a problem. Neale was to play an important role as a former Negro League ambassador to the young boys, but what might he say? I was asked to join Bobo to keep him from saying the wrong thing.

It didn’t take long. A national press conference was scheduled for Petco Park. I had to write a simple speech for Bobo to “thank” Aflac. He was concerned that he’d pronounce Aflac like the duck in their TV commercials. He didn’t want to sound like a fool.

Everything started well… “I’d like to thank Aflac for bringing the All-American Game to San Diego. I’d like to thank Aflac for keeping the history of the Negro Leagues alive. I’d like to thank Aflac for naming the player of the year trophy after Jackie Robinson.”

The talk went smoothly until almost at the end…

“I’d like to thank Ex-Lax for whatever…”

The audience chuckled and honorary chairman Reggie Jackson quipped, “It’s OK, Bobo. Yogi calls it Amtrak.”

Neale was embarrassed, but I convinced him that everybody gets nervous about public speaking. Besides, what’s wrong with being known as the Yogi Berra of the Negro Leagues?

Word about his flub got around and, at an old-timers reunion, Bobo was asked to autograph an Ex-Lax box.

Another story I enjoy involves my grandsons, Joey and Jake Schaeffer. They were Little Leaguers and Bobo came to watch them play. Joey struck out and started to cry. Like a caring grandpa, Neale comforted him by saying that everybody strikes out. Joey was embarrassed because the pitcher was a girl. Neale was sympathetic. “Yeah, but she’s a good pitcher.”

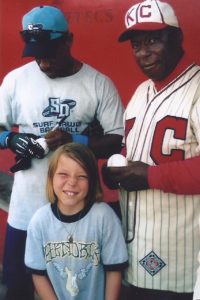

Bobo was asked to throw out the first pitch at a San Diego Surf Dawg’s game in 2005. I got the boys, we picked up Neale and arrived early at Tony Gwynn Stadium. Rickey Henderson was playing for the Surf Dawgs and the grandsons were anxious to meet him.

As things turned out, Rickey was in the dugout when we arrived. He’d never met Bobo before, but they immediately hit it off with one another. The grandkids assumed Bobo was Rickey’s father and Rickey thought that was very funny.

Jake was scurrying about the dugout and found several baseballs wedged into tight crevices. Rickey signed every one of them and was very friendly with the boys.

Rickey Henderson was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009. Later that year, he spoke at a Padres Alumni event in Petco Park. He told the gathering how much he loved playing for the Padres and, when he spotted Neale, said, “There’s my father, former Negro League player Bobo Henderson.”

Neale and I were shocked. Rickey remembered him from four years earlier and remembered that some kids thought he was Rickey’s father. Bobo never tired of telling that story.

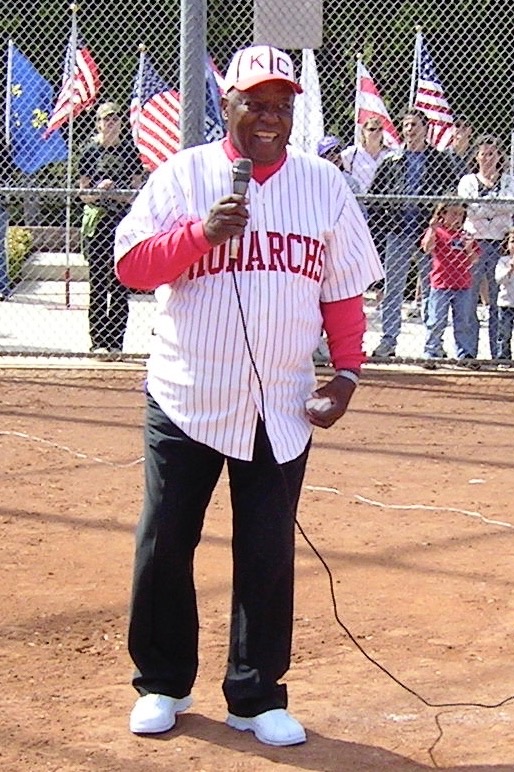

Buck O’Neil was Neale’s manager with the Kansas City Monarchs. Following Buck’s death, a Little League in affluent Carlsbad purchased KC Monarchs and Homestead Grays uniforms for some of their teams. It was a beautiful gesture. Bobo was asked to throw out the first pitch on Opening Day. He signed autographs, posed with the kids and talked baseball.

When it was time for the first pitch, Bobo, the showman, had a colorful routine. Everyone, including Bo, loved his shenanigans.

Everything was perfect until he was handed the mike. Neale was standing on the pitcher’s mound and I was along the first base line.

He began with appropriate comments, but suddenly his tone turned serious.

“I’m mad.”

My only thought was, “Oh (expletive deleted), how can I get out there to grab that mike from his hand?”

But Bobo continued. “During the National Anthem, I noticed that a lot of you boys didn’t remove your caps to honor our flag. That makes me mad. That flag stands for our county, our freedom, our rights. Men have fought and died for our freedom and our rights.”

“Every time the National Anthem is played, you must stand, remove your cap and put your hand over your heart. You must pay respect for our flag.”

Stunned silence was followed by applause and cheers from the grandstand.

As we met on the first base line, Bobo sheepishly asked, “Did I screw up bad?”

I told him, “Neale, that may have been your finest moment.”

Email: Bill@ClairemontTimes.com

To read all the Squaremont columns, visit: